Research Tool - Impact Areas

Rebound Effects

What are rebound effects?

Improvements in the technical efficiency of production processes are a means to reduce resource consumption. However, reductions achieved under real life conditions are usually smaller than what would theoretically be expected under ceteris paribus assumptions. Relevant actors (producers and consumers) will adapt their behaviour to account for the increased efficiencies, often causing additional resource use. This is called rebound- or take back effect. Rebound effects offset part or all of the resource savings that would otherwise be achieved by efficiency improvements. In extreme cases, they can even lead to an increase of total resource consumption (Jevons’s paradox). Rebound effects are mainly explained by economic feedbacks. However, social-psychological factors are also relevant, especially for the consumer side.

Rebound effects can be divided into direct effects, indirect effects and economy-wide effects. They should be taken into account in all assessments dealing with efficiency improvements in order to obtain realistic estimates of resource savings and to adequately inform policy making.

How can rebound effects in soil management be assessed?

To assess rebound effects, it is useful to first determine whether economic or socio-psychological preconditions are fulfilled. Only if the efficiency increases result in lower production costs or affect consumers’ perception of the final products are rebound effects likely to occur. While these conditions are usually met to some degree (and rebound effects therefore common), the actual cost reduction or change in consumers’ perception may be very minor and the size of the resulting rebound effects too small to be of relevance. What effect sizes are considered relevant must be determined individually within the context of a particular assessment.

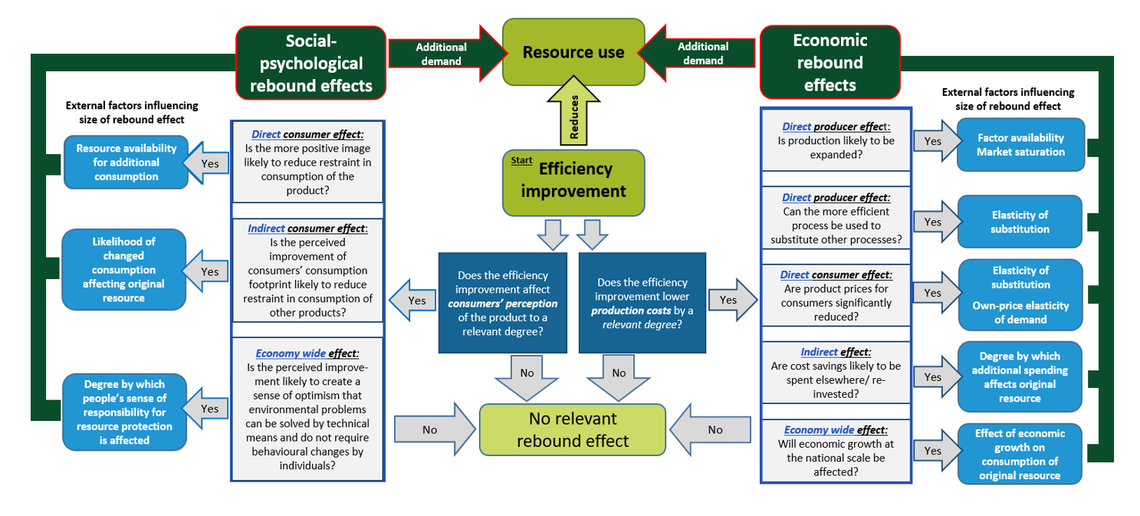

Paul et al. (2019) present a framework for assessing rebound effects in agricultural land and soil management (Figure 1). Similar to a flow chart, users can answer “yes” or “no” questions to find out whether the occurrence of different rebound types is likely. Factors determining the size of the rebound effects are given in blue boxes.

There is scientific consensus regarding the existence of rebound effects, but little agreement on their size. Values provided in scientific literature for increases in energy efficiency vary considerably (for an overview of studies, see Huesemann & Huesemann, 2008 and Kolstad et al., 2014). However, while it is difficult to estimate effect sizes, the implicit assumption of zero rebound effects made by studies that choose to ignore them is not supported by scientific evidence (Maxwell et al., 2011). Because rebound effects result from changes in the behaviour of different actors and are based on multiple variables, it is challenging to assess their effect size (particularly in ex-ante assessment). In many cases, only a very rough estimate will be possible. For rebound effects resulting from economic feedbacks, general equilibrium models can help to estimate reactions of market participants. For rebounds due to social-psychological factors, a major research gap exists (Maxwell, 2011). The use of the rebound effect assessment framework (Paul et al., submitted) may facilitate an assessment of rebound effect sizes.

In general, the following factors are considered to be positively related with the size of rebound effects (de Haan et al., 2015):

• Relative size of the efficiency improvement (%)

• Relative share of savings of total production costs (%)

• Degree to which production is limited by availability of the more efficiently used resource (e.g. limited allocation of irrigation water, limited amount of allowable fertiliser application)

• Degree to which the more efficient process can be used to substitute other production factors

• Relative price reductions for the final product (%)

• Degree by which the consumption of the product is perceived as more positive (e.g. social or environmentally friendly) than before

• Demand elasticity, degree to which is demand is currently unsaturated

• Low degree of other costs associated with product consumption (e.g. in the field of mobility, travel-time is often more relevant than travel-cost)

• Degree to which the more efficiently used resource is also used in the production of alternative goods and services (the demand for which might increase with increasing wealth)

• Degree to which the more efficient resource use triggers technical innovation in other sectors

Figure 1: Framework for assessing economic or socio-psychological rebound effects from efficiency improvements. Factors determining the size of the rebound effects are presented in the blue boxes (Paul et al., 2019).

References

De Haan P, Peters A, Semmling E, Marth H, Kahlenborn W. 2015. Rebound-Effekte: Ihre Bedeutung für die Umweltpolitik. TEXTE 31/2015, Umweltbundesamt, Dessau-Roßlau, 112 pp.

Huesemann M H, Huesemann J A. 2008. Will progress in science and technology avert or accelerate global collapse? A critical analysis and policy recommendations. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2008, 10, 787–825, DOI:10.1007/s10668-007-9085-4

Kolstad C, Urama K, Broome J, Bruvoll A, Cariño Olvera M, Fullerton D, Gollier C, Hanemann W M, Hassan R, Jotzo F, Khan M R, Meyer L, Mundaca L. 2014. Social, Economic and Ethical Concepts and Methods. In: Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Edenhofer O, Pichs-Madruga R, Sokona Y, Farahani E, Kadner S, Seyboth K, Adler A, Baum I, Brunner S, Eickemeier P, Kriemann B, Savolainen J, Schlömer S, von Stechow C, Zwickel T, Minx J C (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA.

Lambin E F, Meyfroidt P. 2011. Global land use change, economic globalization, and the looming land scarcity, PNAS, 108 (9), 3465–3472. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1100480108

Loch A, Adamson D. 2015. Drought and the rebound effect: a Murray–Darling Basin example. Natural Hazards, 79, 1429–1449. DOI:10.1007/s11069-015-1705-y

Maxwell D, Owen P, McAndrew L, Muehmel K, Neubauer A. 2011. Addressing the Rebound Effect, report for the European Commission DG Environment, 26 April 2011.

O’Brien D, Shalloo L, Crosson P, Donnellan T, Farrelly N, Finnan J, Hanrahan K, Lalor S, Lanigan G, Thorne F, Schulte R. 2014. An evaluation of the effect of greenhouse gas accounting methods on a marginal abatement cost curve for Irish agricultural greenhouse gas emissions. Environmental Science & Policy, 39, 107–118. DOI:10.1016/j.envsci.2013.09.001

Research Tool

- Impact Area Selection

-

Rebound Effects

- Soil contamination and human health